Water Contamination Latin America El Agua en Latinoamerica Arte Political

When we consider the troubling, oft tragic problem of global h2o shortages, our minds naturally pivot to regions of the world typified past parched, landlocked terrain.

Nosotros might think of Africa, with its perennial media images of malnourished and dehydrated communities. We might recollect, also, of the Middle Eastward, with its sunday-scorched climate, which recently experienced its worst drought in ix centuries.

Nosotros wouldn't necessarily consider, at to the lowest degree non without some time or prompting, Latin America. Withal, in water terms Latin America falls foul of a grim irony – it is a region with abundant water sources just is as well a region where some 36 million people lack access to drinking water.[1]

Water does more than than keep us hydrated. It grows our crops, powers our industries and cleanses our homes. All the same up to 100 meg people in Latin America lack access to sanitation, according to international think tank the World Water Quango (WWC); factor in those reliant on latrines or septic tanks and that figure rises to 256 million.[2] Untreated sewage goes on to pollute underground aquifers, rivers and lakes.

Water does more than than keep us hydrated. It grows our crops, powers our industries and cleanses our homes. All the same up to 100 meg people in Latin America lack access to sanitation, according to international think tank the World Water Quango (WWC); factor in those reliant on latrines or septic tanks and that figure rises to 256 million.[2] Untreated sewage goes on to pollute underground aquifers, rivers and lakes.

With depressing predictability, inequality rears its caput to exacerbate these problems. WWC figures evidence that poorer sectors of the population pay between 1.5 and 2.8 times more for their water than wealthier families – all for a lower quality of water more likely to harbor diarrheal diseases.

Nor exercise the issues terminate there. The region's ground water suffers from relentless exploitation. In Mexico, for example, 102 of the nation's 653 aquifers – or clandestine water sources – are classed as over-used, threatening the main water source for two-thirds of the population. Across South America, around one-half of all water comes from aquifers subject field to increasing pollution from commercial uses.

For those seeking to address some of these dangers the clock is ticking, because flesh's impact upon the natural globe means today's problems could be tomorrow'southward calamities.

Global warming and drought: a climate of fear

The passage of time, coupled with the march of climate change, is simply serving to compound Latin America'south growing water crisis.

© Louis Lliboutry; Alex Cattan and Marc Turrel

Glaciers, ane of the region'south fundamental sources of fresh water, are melting due to global warming. In areas such as the Real Range in Bolivia or the White Range in Peru, the expanse widely covered by glaciers has shrunk by around one-third since the mid-nineteenth century.[3]

Chile is a case in point. It has one of the world's largest reserves of fresh water outside the northward and due south poles, simply its abundant glaciers – lxxx% of South America's glaciers are in Chile – are melting fast. More than vii million people living in and around the uppercase, Santiago, rely on the glaciers to feed about of their water supply in times of drought. But a toxic combination of rising temperatures, a 10-twelvemonth mega-drought and increasing exploitation, is proving lethal and the water ice mass is now retreating one meter per twelvemonth on average.

Less than ii decades from at present, some glaciers will have disappeared, while the total volume of all glaciers in Chile volition have shrunk by half by the end of the century.[four]

Hurricanes, their frequency and intensity strongly linked to climate modify[5], will further imperil water supplies in the region. Contempo history contains a stark precedent, with Hurricane Mitch in 1998 killing 9,000 people in Central America and dislocating 75% of Hondurans.

Farther s, changes in the behavior of the El Niño ocean current could affect weather patterns and bring even more severe droughts to communities.

The United nations reports that since 2013 South America's largest urban center (Sao Paulo, Brazil: population 11 million) has been caught in its almost severe drought for 80 years.[vi]

All of these changes, all of these challenges, must also be seen in the context of ascension population numbers. The UN estimates the population of Latin America (including the Caribbean) increased from 287 million to 648 million between 1970 and 2019.[7] Since 2010 the region has experienced population growth of around x%. The WWC notes that "many major lakes and river basins from Northward to Southward America are nether great strain from growing populations and resulting accumulated agronomical and industrial run-off". [eight]

A generation from now the outlook could be fifty-fifty more fraught – and the problem is hardly unique to Latin America.

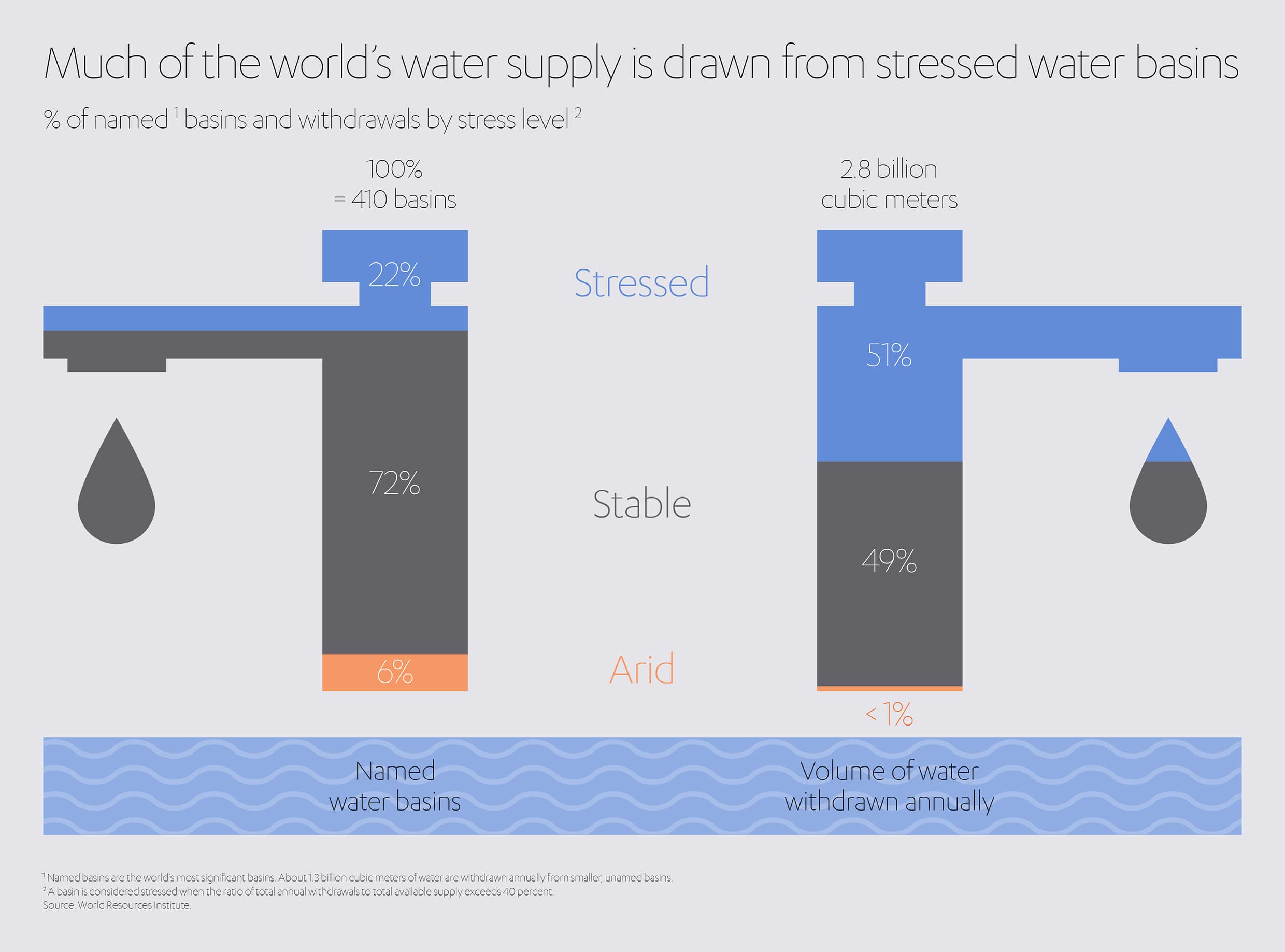

Estimates suggest that by 2030 global water basin supplies could decrease by 10%, or 25% by 2050.[nine] Worldwide, water utilise has increased by approximately 1% each year for the last 30 years, with more two billion people at present living in countries experiencing high water stress.[ten]

Water challenges converge in perfect storm

While acknowledged as a region-wide problem, the characteristics of Latin America's water challenges differ on a nation-by-nation basis. They are dictated past factors as diverse every bit politics, economics, topography, culture and history.

Chile, once again, exemplifies many of the h2o difficulties faced by South America.

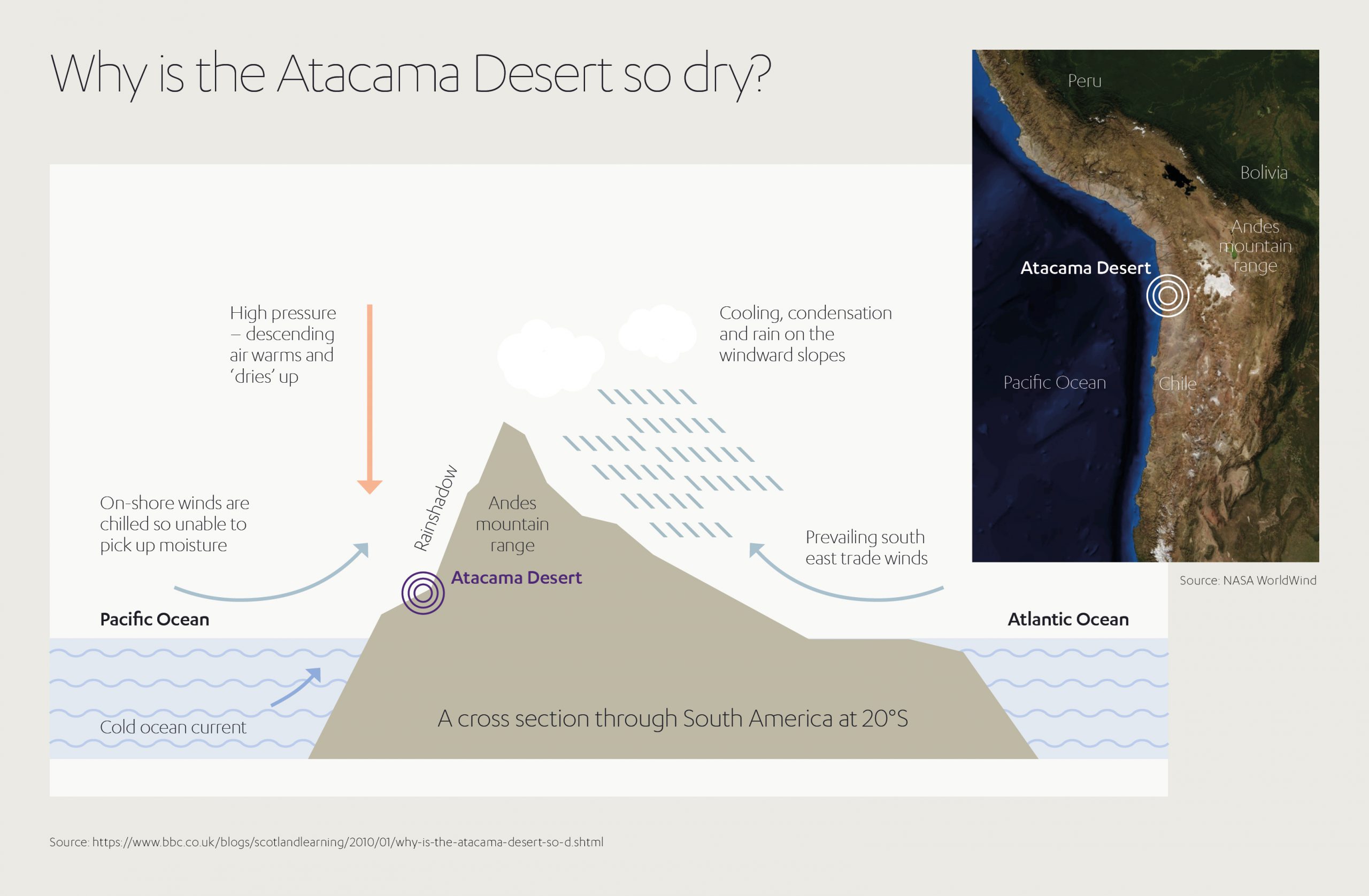

Its due north is overwhelmingly, near uniquely, arid. The 100,000 foursquare kilometer Atacama Desert is the driest place on Earth.

The Andes mountains to the east causes clouds to ascent and condense before reaching the desert basin, while the Pacific Bounding main to the westward is too common cold to allow on-shore winds to collect wet; hence the Atacama by and large experiences measurable rainfall merely once a century. The nearby coastal city of Antofagasta (population: 350,000) records an average precipitation of just 1mm per year.[11]

Further to the south, climate change was blamed for destructive unseasonal rainfall in 2017. The resulting floods deprived more than a meg people in the Chilean uppercase of Santiago of piped water.[12] Santiago is too tipped to experience severely reduced water supplies in the future.[xiii]

That drench arguably brought to an stop Central Chile'south 'mega-drought', during which the Majestic Meteorological Society noted the region (and its 10 million+ inhabitants) had experienced "an uninterrupted sequence of dry years since 2010 with mean rainfall deficits of 20 – 40%".[14]

Confronting this backdrop lies some other challenge: in some parts of Chile more than 80% of water is privately controlled and earmarked for industry and agriculture. This, co-ordinate to charity the Latin American Bureau, leaves many Chileans facing a shortage of drinking h2o, while besides contaminating sources with industrial waste.[xv]

In the same yr Santiago was hit by freak flooding, Bolivia experienced months of drought which led to empty reservoirs, water rationing in major cities and protests in the streets. A country of emergency was declared beyond the land – a country which according to the United nations has already lost 40% of its glaciers to melting in the last two decades. While climatic change is at least partly culpable, government policies shared some of the arraign, cheers to a huge increase in h2o-intensive industries such as soya growth, along with intensive deforestation.[16]

In Peru, grassroots environmental groups have accused international mining companies of commandeering water resources, cut supplies to farmers, and polluting rivers.[17] Unrest is growing, and in 2016 strikes and clashes over claims of h2o hijacking saw 2 provinces declare martial constabulary.[xviii]

Information technology is a similar story in Ecuador, where farmers are suffering as agribusinesses and mining companies capitalize on a 2015 police force allowing further water privatization and exploitation of deficient supplies. The Ecuadorian constitution is unique in enshrining water every bit a homo correct, but farmers and environmentalists have been compelled to march on the uppercase, Quito, demanding equal access. Academic Manuela Picq has stated that Republic of ecuador'southward wealthiest 1% control 64% of fresh h2o and says "a single mine tin can apply more water in a day than an entire family in 22 years".[19]

In Guatemala, meanwhile, evidence is mounting that h2o shortages are driving internal migration. Communities are abandoning areas left dry out by corporations sucking up freshwater resource and diverting rivers. The corporations are oftentimes immune from prosecution due to weak governance – an example, says the country's ex-vice-president Eduardo Stein, of the state working 'in the interests of a chosen few' and causing widespread anger.[xx]

Partnerships, expertise and long-term thinking

Such poor resource management is thrown into abrupt relief elsewhere in Latin America, where interventions to improve distribution are having tangible impacts on daily lives.

In communities in Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil, for instance, thousands of schemes take been funded to ameliorate the network of clean water supplies in long-neglected rural areas.

Women in detail have benefited. No longer expected to walk many miles for h2o daily, they can at present devote more than time to farming – with dramatic results. Women's input has increased agricultural income and nutrient security on a home-by-dwelling, village-by-hamlet basis, leading to an average 30% rise in family incomes.[21]

Brazil is increasingly regarded as a standard-bearer for positive activeness to improve water access. Favoring a multi-stakeholder approach, the rights of all interested parties (supply companies, free energy providers, irrigators and civil groups) to partake in policy decisions has for more than two decades been enshrined in both federal and country police force.

In fact, enormous progress has been noted across the Latin American region in extending water access over the by decade, with the World Bank recognizing "70 million more people served in the urban centers than at the turn of the millennium".[22]

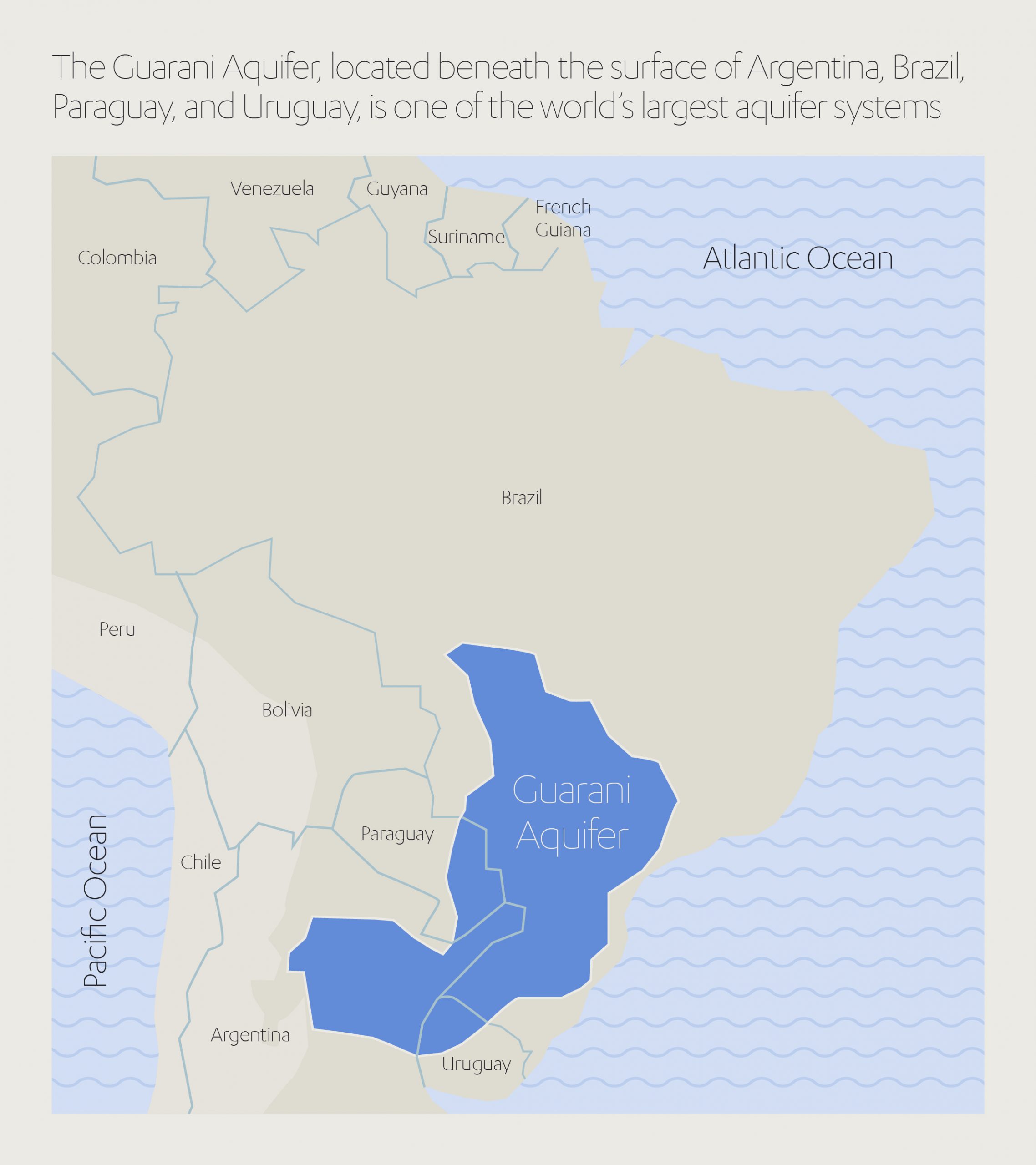

Cross-border collaboration has been at the forefront of many notable advances. The Guarani Aquifer Arrangement (SAG), one of the earth'due south largest basis water reservoirs, holds some 37,000 cubic kilometers of h2o in its ane,190,000 square kilometer expanse spanning Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay. A competitive attitude to this invaluable resource could take led to depletion and pollution, but the four countries united in 2001 on an environmental protection and sustainable development programme to safeguard the SAG in the long-term.[23]

The U.s.$ 26.7 1000000 plan has successfully orchestrated several key policies: gathering together scientific and technical understanding of the SAG; improving groundwater direction; promoting public involvement and better communication; and assessing the SAG'due south potential for geothermal free energy.

Equally a result of this unique international partnership, it is hoped the SAG will continue to provide people and businesses with freshwater supplies for generations to come and may fifty-fifty serve as a model for elsewhere in the region.

With such success stories to spur momentum, the door is open up to the private sector to play a greater leading role in overcoming the region's persistent water challenges.

Contract demonstrates scalability of Almar model

Almar Water Solutions, part of Abdul Latif Jameel Energy, is at the forefront of efforts to tackle water adversity across Latin America, specially in its driest areas, such equally Chile.

Almar is apace expanding its footprint in the region through its 2019 acquisition of water treatment company Osmoflo SpA. In August 2020, Almar, via Osmoflo, won a three-yr water services operation and maintenance contract for Chilean mining company Mantos Copper.

Almar will operate a water treatment plant for the client's Mantos Blancos project in northern Chile, just 45 kilometers north of that notorious dry out-spot, Antofagasta. The desalination establish will utilise reverse osmosis to produce water suitable for the kind of mining activity which can bring more than jobs and prosperity to the region.

CEO, Almar Water Solutions

Almar's purchase of Osmoflo SpA marked the company's kickoff major foray into the Latin American water services market and offers new potential for solving the region'southward urgent water challenges. Along with performance and maintenance contracts comes a armada of multi-capability mobile h2o treatment units providing clients with curt-term or emergency purification solutions.

"Almar tin can use this experience in Chile as a springboard for other Latin American projects," said Carlos Cosin, CEO of Almar Water Solutions. "Indeed, a further contract is set up to be appear shortly, finer doubling the size and value of our conquering. The deal, which supplements our portfolio of desalination, drinking water treatment, wastewater purification and industrial h2o operations, demonstrates our aggressive plans for the hereafter."

Worldwide problem demands visionary response

To achieve great things, to bring nearly real change, it is imperative to aim high.

If we can ameliorate the water regime of a supremely h2o-challenged country similar Chile, we can tackle the water challenges of the whole of Latin America. And if we tin kickoff the environmental, technical and historical water hurdles of Latin America, we can widen our scope to other emerging markets around the world with every bit pressing needs.

As such, since its foundation, Almar has likewise been combating water scarcity and contamination across the Middle Eastward and Africa.

Tardily 2018 saw it secure a deal to produce the offset-ever large-scale desalination plant in Kenya, delivering 100,000 cubic meters of drinking water to more than one one thousand thousand people in Mombasa.

In Kingdom of saudi arabia, it won a contract in January 2019 to develop Shuqaiq 3 IWP well-nigh the Red Sea city of Al Shuqaiq. I of the earth'southward largest desalination plants, the US$ 600 1000000 Shuqaiq three will deliver 450,000 cubic meters of clean water each solar day to more than than one.viii million people and create 700 associated jobs.

Then in May 2019, Almar caused a major pale in the Muharraq plant in Bahrain, with a 29-year contract to operate the 100,000 cubic meter/day wastewater treatment plant and sewerage system. The canalization system includes the first 16.5 km deep main gravity collector in the Gulf region, along with a sewage collection network.

Almost recently, Almar H2o entered into a joint venture with Hassan Allam Utilities in Egypt to form AA Water Developments, to help revitalize the land's water infrastructure. This led to the acquisition of Ridgewood Group, Egypt, a major desalination services company. Ridgewood operates 58 desalination plants throughout the country, with a focus on industry and tourism – a critical sector for Arab republic of egypt's economy. This network of facilities has the capacity to provide 82,440 cubic meters of safety, clean drinking water every unmarried day. The acquisition continues Almar'south strategy to expand speedily across its portfolio of new greenfield projects with desalination, water handling plants and other existing (or and then-called brownfield) water infrastructure assets which are already in functioning, to drive efficiency and growth in access to sustainable h2o solutions.

These groundbreaking collaborations, together with rapid expansions of operations in Chile, demonstrate Almar'south deep commitment to securing for futurity generations a more equitable 'h2o world'. A globe in which everyone, whether their needs are domestic, agronomical or industrial, has admission to sustainable resources necessary to improve their quality of life.

Deputy Chairman & Vice President

Abdul Latif Jameel

"Information technology is ironic that in our world, a planet of vast h2o resources from oceans to ice caps, only a tiny fraction is available to support life, including us, while huge parts of the planet's inhabitants lack enough water to live on, much of the time due to our own mismanagement of resources" commented Fady Jameel, Deputy President and Vice Chairman of Abdul Latif Jameel.

"Information technology is clear that a considered and cohesive approach across business and governments, together with swift action is needed to tackle this result – and the sooner the better."

[ane] https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/characteristic/2015/03/20/america-latina-tener-abundantes-fuentes-de-agua-no-es-suficiente-para-calmar-su-sed

[2] https://www.worldwatercouncil.org/fileadmin/wwc/News/WWC_News/water_problems_22.03.04.pdf

[3] https://world wide web.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2015/03/20/america-latina-tener-abundantes-fuentes-de-agua-no-es-suficiente-para-calmar-su-sed

[iv] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2019-08-14/south-america-s-glaciers-may-have-a-bigger-problem-than-climate-change

[five] https://www.pnas.org/content/117/22/11975

[6] https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2015/01/06/36-millones-latinoamericanos-acceso-agua-potable-brasil

[7] https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/Files/1_Indicators%20(Standard)/EXCEL_FILES/1_Population/WPP2019_POP_F01_1_TOTAL_POPULATION_BOTH_SEXES.xlsx

[8] https://www.worldwatercouncil.org/fileadmin/wwc/News/WWC_News/water_problems_22.03.04.pdf

[9] https://www.mckinsey.com/concern-functions/sustainability/our-insights/water-a-human-and-business organization-priority?cid=eml-spider web

[10] https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000367276/PDF/367276eng.pdf.multi

[11] https://en.climate-information.org/south-america/chile/ii-region-de-antofagasta/antofagasta-2064/

[12] https://world wide web.theguardian.com/world/2017/feb/27/chile-floods-millions-of-people-without-water-in-santiago

[thirteen] https://www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2017/mar/01/h2o-scarcity-latin-america-political-instability

[14] https://rmets.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/joc.6219

[xv] https://lab.org.great britain/chiles-water-crisis/#:~:text=Water%20is%20unevenly%20distributed%20throughout,government%20is%20refusing%20to%20address.

[16] https://amp.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2017/mar/01/water-scarcity-latin-america-political-instability

[17] https://www.pri.org/stories/2017-01-04/la-paz-brusk-water-republic of bolivia-s-suffers-its-worst-drought-25-years

[18] https://perureports.com/chimbote-land-emergency/4384/

[19] https://amp.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2017/mar/01/water-scarcity-latin-america-political-instability

[twenty] https://amp.theguardian.com/global-evolution-professionals-network/2017/mar/01/water-scarcity-latin-america-political-instability

[21] https://world wide web.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2012/08/28/investimentos-agua-nordeste-mulheres

[22] https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/characteristic/2013/03/22/world-water-day-latin-america-achievements-challenges

[23] https://www.caf.com/media/8257/water_agenda_south_america-caf.pdf

Source: https://alj.com/en/perspective/torrent-of-problems-water-challenges-of-latin-america/

0 Response to "Water Contamination Latin America El Agua en Latinoamerica Arte Political"

Post a Comment